Air Raid Shelters and Air Raid Warden Posts

Communal shelters

The need to provide shelter for citizens caught in the open when an air raid started was realised before the start of the Second World War, so in 1938 trenches were dug in Regent’s Park that had room for 6,000 people and in Primrose Hill for 2000. Unfortunately, they were usually very damp. The Zoo, (which closed on the outbreak of war but reopened within a month, and stayed open throughout the war), had shelter for 1,000 people.

Arthur Simons, a St John’s Wood resident, remembers that:

One of the most used shelters was Oslo Court which was improvised from a garage. My family were regular users of the shelter until the end of the war. It was fitted out with cubicles with 2-tier bunks, so was quite comfortable. Most of the occupants were out of Barrow Hill Road and Newcourt Street.

Bentinck Close, one of the blocks of flats just north of Regent’s Park, was also well prepared. There was an air raid shelter in the basement with room for all tenants, equipped with the latest system of gas filtration and ventilation plant, operated in the first place by a diesel engine, and in the event of its breakdown, by pedal cycles. Water was provided independent of the ordinary supply and there was adequate provision for male and female lavatory accommodation. There were bunks for sleeping and emergency food and medical supply for up to four or five days. But in the event the flats were requisitioned for the RAF crews training at Lord’s and the original tenants had departed before bombing began.

Once the War started St Marylebone Borough Council constructed an air raid shelter in the crypt of St John’s Wood chapel (now church), although the faculty authorising the rector and church wardens to grant a license was not actually granted until 7 August, 1941. As Rose Watt of Townshend Cottages recalled, sometimes the crypt was so crowded people had to stand all night; at other times they wheeled bedding along in a pram and also took a cup so that they could get some Oxo to drink. One night bombs fell on the burial ground.

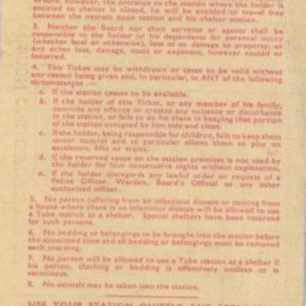

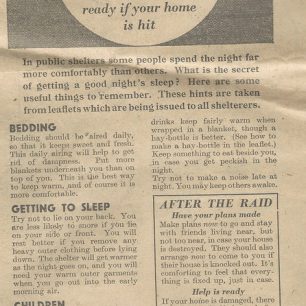

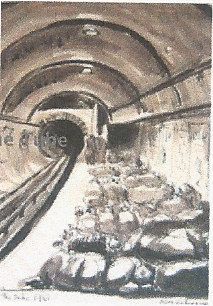

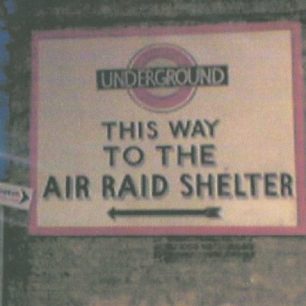

St John’s Wood tube station was one of the many Underground stations that was taken over by the public when night bombing began, despite this being banned by the Government. People just bought a ticket and went down to the platforms as the last trains left and refused to leave; they later set up camp on a more organised basis. Soon the Government capitulated and welfare organisations provided canteens and libraries, and bunks were installed. This ticket was issued to Miss M Chandler in 1944 and allowed her to use the station during air raids. There was a list of conditions that people had to meet including making sure that bedding and clothing was clean and that children were kept under control away from escalators and trains.

Verily Anderson in Spam Tomorrow describes how she and her husband and two babies fled to the station at midnight when their house in St John’s Wood Park had been subjected to a prolonged attack of incendiary bombs which spluttered silver fire in their garden. I could hear them bouncing off the roof. We leaned over the babies with our backs to the now open window as another bomb came down and another. We could hear a plane dive just above us. The guns clatttered out, shaking the house again. [When they reached the station] inside the circular entrance to the station, lights glowed and quietness soothed. The escalators were stationary. We left the prams at the top and walked down, carrying the babies and hiding the kitten in their shawls, in case animals were not allowed in public shelters. On the platform regular shelterers slept on steel and wire netting bunks. Donald stretched himself out beside the baby and they went to sleep at once. Marian and I tossed around on our wire-netting, to the roar of the air-conditioning appliance which drowned all sounds from above. We must have fallen asleep just before the first train rattled through the station at about six. From then onwards they ran every ten minutes, disturbing sleep like a recurring cough. The shelterers began to stir, gather up their blankets and carry them away. The escalator, working now, took us to the upper air. A warden at the top gave the welcome information that all was clear.

But many people could not stand the lack of privacy and peace and preferred a private shelter. Conversely others, like the Disson family in St Johns Wood Terrace, started with a private shelter but changed to a public one.

We had an Anderson shelter in the back garden, this consisted of a hole dug into the ground, then curved corrugated iron being placed over and topped off with the soil from the hole, the inside had four bunk-beds, safe but never much use should a bomb drop nearby, eventually because of ‘shelter rash’, damp and the limited amount of room in the Anderson we migrated to the shelters in the street two of which were in the Terrace, a brick one built in the roadway opposite Ordnance Hill and a concrete one opposite Aquila Street, we soon found out that all of the bunks in the these were booked with some people even spending all day in there, so no room at the inn; next stop was the St Johns Wood tube station, again all bunks were taken but we found a vacant spot on the floor in the weighing scale recess, (no chance of rolling onto the tracks from there), on the south bound Bakerloo platform, it was there that we spent most nights for the rest of the war. (John Disson)

Although not heavily bombed compared with some parts of London, St John’s Wood was one of the worst hit areas in January 1943 when the Germans carried out reprisals for an RAF raid on Berlin; Marylebone station was closed and Hampstead Tube station put out of action at the same time. St John’s Wood also suffered quite heavily from flying bomb damage in 1944.

Private shelters.

Small brick built shelters, a tiny version of the public shelters that had been provided in the streets, began appearing in people’s gardens – some of these also had an extra opening in case the door was jammed by falling masonry outside. One shelter remained in St Johns Wood Terrace until 2011 and another is still in use as a store in a garden in Woronzow Road.

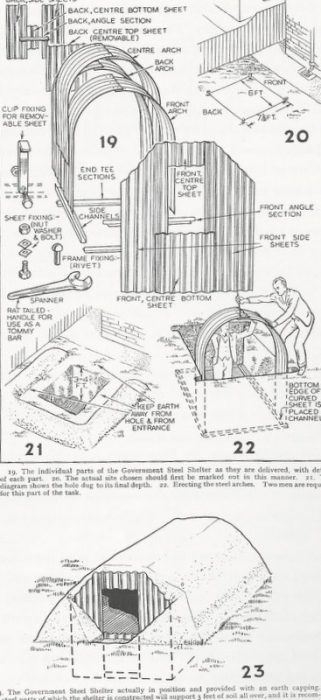

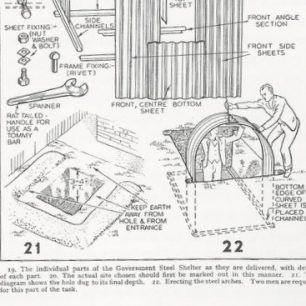

An Anderson shelter was the most common form of domestic shelter, named after the, then, Home Secretary, Sir John Anderson. By Sept 1940, 2,300,000 had been produced, sufficient for a quarter of the population to shelter in. They were free for those earning under £250 per year, and cost £7 for others. The shelter had six curved steel sheets bolted together to form an arch, flat steel plates at either end, one of which could be unbolted for an emergency exit, and a hole through which one climbed down, for the Anderson was buried 4 foot down in the garden with at least 15 inches of earth on top . It was 6 foot 6 inches long, 4 foot 6 inches wide and 6 foot high, and could shelter two people lying down, or 6 people sitting. A handy extra was that the earth on top could be used for growing flowers or vegetables. It proved tough enough to withstand anything apart from a direct hit, but was always damp. George Peerless, who won the George Medal for bravery in rescuing bombed neighbours, had an Anderson in his garden in Aquila Street.

Erecting an Anderson shelter

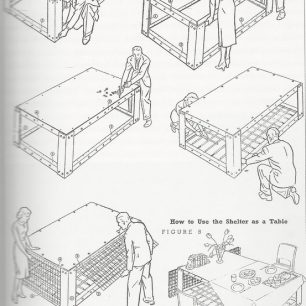

More and more people wanted to stay in their own home during a raid so Herbert Morrison commissioned the indoor shelter, named after him. It was a steel table 6 foot 6inches x 4 foot wide and 3foot 9inches high with a steel mattress along the bottom and wire mesh at the sides,. It could be used as table in the daytime and be used as a bed for 2 adults and 2 children at night. 1,100,000 were supplied by end of war, free to those earning under £350 p.a .and became the most popular shelter, being particularly useful when flying bombs arrived and there were only a few seconds in which to find cover. When the flats at Wharncliffe Gardens were directly hit in August 1944, Miss Madge Hunt, whose mother and sister were both killed, wrote later:

We heard the terrible screech of the bomb. the next thing I knew I was pinned from my shoulders to my right arm across my chest, my left arm was free and I could just move that and was able to put it out at the side a little way.

She was crippled for the rest of her life.

Wharncliffe Gardens August 1944

[www.bbc.co.uk/history/ww2peopleswar/stories/66/a3489366.shtml]

At No 8 St John’s Wood Park, author, Denis Wheatley, heard Neville Chamberlain’s announcement of the outbreak of war in September 1939 and realised that his house was old and lacked steel girders, so would probably collapse if hit by a bomb.

But running along the back of the semi-basement there was a three-foot-wide , four-foot- deep stone trench, and the bay of the drawing room window jutted out above it, supported by two stout pillars.

He constructed an air raid shelter from empty champagne cases filled with rubble and reinforced with cement, and stacked them between the pillars and along the outer side of the stone trench, then used more rubble with the cement for concrete to reinforce them.

With other cases I made three stacks to support the ceiling of the servants’ sitting room, through the window of which we could climb out into the shelter. In it there were bedding, food, wine, books and ample space for ourselves, our Scottish cook and two pretty young Irish sisters, who were our maids.

Clifford Heathcote’s family stayed in the cellar My family lived on Woronzow Road (some still do I think!) and tales of the war years were handed down to me by my mum. My great grandfather had a builders yard (Joseph Disson & Son) near the junction of Woronzow Road And St. John’s Wood Terrace and built a shelter for the family there. Only one small problem: the guns on Primrose Hill. My great grandmother was a strapping woman who would have given Herr Hitlar a right pounding and had no fear of his bombs, but as soon as those guns started she would freeze rigid and if the sirens were late, the family would be left to carry her down the road to the shelter while all hell rained down from above. Ultimately they took to sheltering in the cellar of their house at number 18, but this nearly ended in disaster when a string of bombs came down on Henstridge Place stopping only 100ft or so from them.

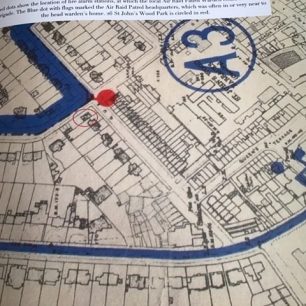

Air Raid Warden posts

The whole area was divided into sections with wardens and a head warden who had to ensure that all properties had their blackout curtains drawn. If bombs were dropped nearby the warden had to check for damage, and if fire broke out, had to call the Fire Brigade from a special Fire Alarm post (sometimes as in Queens Terrace, a telephone box).

Murder in an air raid shelter

Shelters did not always provide protection, and the night time black out conditions in London could be used to advantage by predators other than the Luftwaffe. Gordon Frederick Cummins (1913 -1942), known as the Blackout Killer, and the Blackout Ripper, used a shelter as the venue for the first of four murders and two attempted murders he committed within five days in February 1942. Although born in Yorkshire, he was a resident in St John’s Wood at the time.

Cummins was a leading aircraftman in the RAF when he volunteered to retrain for aircrew duties and was posted to RAF ACRC (Aircrew Reception Centre), based at Lord’s and Regent’s Park, London, where serving members of the RAF and new recruits were assessed for training. His intake ran from the 2 to 25 February 1942. On Sunday 9 February 1942, the body of 40 year old pharmacist, Evelyn Hamilton was discovered in an air raid shelter in Montagu Place, in St Marylebone. She had been strangled and her handbag stolen

On Monday 10 February, the naked body of 35 year old Evelyn Oatley (also known as Nita Ward) was discovered in her flat on Wardour Street. As well as having been strangled, her throat had been cut and she had been mutilated. The next day, Margaret Lowe was strangled and mutilated in her flat in St Marylebone, followed on 12 February by the strangling and mutilation of Doris Robson in the flat she shared with her husband.

On Friday 14 February 1942 came two attacks on women who managed to fight their attacker off, but unfortunately for Cummins, when he ran away from Greta Hayward, he left his gas mask case behind, and it had his service number 525987 on it. He was arrested on 16 February and when his quarters were searched various items belonging to his victims were found and his fingerprints were discovered in two of the victims’ flats. After a one day trial at the Old Bailey, in April, the jury took only 35 minutes to find him guilty, and he was executed on 25 June 1942, during an air raid.

Comments about this page

Chalcot Square, a very expensive area now, was a public shelter during the war. I used to watch it being demolished on my way home from Princess Road school as I lived in the basement flat of 8, Rothwell Street. Now valued at £3,000,000 plus.

I was on Primrose Hill late summer 1944 when a doodlebug landed close to Regents Park Road. I have found no reference to it. Help please.

I’m looking for information on the doodlebug attack on St. John’s wood station. Doris Sartain was the female survivor. Date is sept 1940. A unknown baby also survived the rest including sarah jane Sartain, William (billy) Sartain and Benjamin Sartain were amongst the dead the men were in the pub when it hit. Any information would be greatful.

I lived at 19 Belgrave Gardens during the war. I was born in 1939 but have many memories of it. I seem to remember big grey concrete buildings put up in the road for air raid shelters and being picked up when the air raid warning sounded and running across the road to one of these buildings. Also, I can still see it now, we were playing outside the Belgrave [Pub] when a doodle bug came straight down Abbey Road with two planes following it, but we just watched until it went out of sight and [we] carried on playing. I don’t know where it landed but it was heading toward Hampstead

We lived at 16 Newcourt Street and I can remember going down to the Oslo court shelter and to the St. John’s Wood Underground station. We didn’t get much sleep on those occasions so we had first an outdoor Anderson shelter in the garden and then an indoor Morrison shelter.

I lived in 88 St. John’s Wood Terrace from 1942 until 1952. We had the middle floor and two other families lived there with us. Please comment, Ken.

I was a small child during Word War II in London. My parents, brother and sister and I lived in a St John’s Wood apartment block (2 bedroom fifth-floor walk up apartment). Name of the apartments was Wharncliffe Gardens. Our apartment block was bombed on the north end. We lived on the south end. We had above-ground shelters between the blocks of apartments They would not have survived a direct hit.

There was a brick above ground shelter at the beginning of St John’s Wood Park We lived opposite but the basement of our house was shored up with bolts of wood just like pit props.

Arthur Simon, you haven’t left your email, and we would very much to talk to you. Please leave your email so that we can contact you. Do you still live in the area? Jane

One of the most used shelters was Oslo Court which was improvised from a garage. My family were regular users of the shelter until the end of the war. It was fitted out with cubicles with 2 tier bunks, so was quite comfortable. Most of the occupants were out of Barrow Hill Road and Newcourt Street.

Gordon Cummins was living in Viceroy Court at the time.More details can be found in a book by Max Allan Collins, author of “The Road to Perdition, The London blitz Murders” although it is a mix of fact and fiction.

Add a comment about this page