Neville J. Peerless (1925 -1997) Memoirs of a childhood in Aquila Street in the Wood

Jane Peerless Baldwin wrote: My father Neville grew up in St. John’s Wood from the mid 1920s until the early 1940s. The memoir was written in the form of a letter in 1987 to his baby daughter, Allison. Neville joined the Navy during World War Two and then having married Margaret Pepper emigrated to Canada with daughter Jane in the 1950s and later went to Colorado to be nearer Margaret’s sister and had more children. David married Irene and lived at 2 Aquila Street until the 1990s . My mother (Margaret Pepper) and Neville divorced in the early 1970s and he married again and Allison was born in 1986. He was soon diagnosed with colon cancer and I assume he wrote the memoir realizing that he would not live until Allison was an adult. He died 10 years later in August of 1997.

The Memoir

The family

Dearest Allison,

I am writing this now to you, so that at some future time, you will be able to know more about your dad, and have a little history about my life. I was born on April 28 1925 in an old brick two storey house – 3 St Johns Wood Terrace, St Johns Wood, a small suburb of London, England. I was one of twin boys. I was named Neville John Douglass and my twin brother David George Edward. Too many names you may think, but it was the custom in those days to name children with names of close relatives and family. By the way, my brother Dave was the one to be born first. In fact, he is exactly 3 minutes older than I. He was so tiny at birth that Dr. Colt (my mum’s doctor) thought he was a girl, and signed the birth certificate in error that we were boy and girl twins. Of course, the error was at once corrected.

My dad’s name was George Edward Peerless; Dad was born in 1888 and served in the British Army as a private in the King’s 17th Lancers (the Death and Glory boys) for many years before his marriage; (in the 1911 census he was in India and the regiment returned to Europe at the start of the First World War, after which he was awarded the Victory medal and the British War medal) He married my mother, Alice Maud Palmer, at All Saints Church, Finchley Road , St Johns Wood on 22 April 1922 , when he was living at 68 Boundary Road. Dad was a small man in stature, but a giant in every other way. ( George Peerless was one of the first civilians to be awarded the George Medal for rescuing his neighbours from a bombed house in St John’s Wood.) A very good looking man, rather swarthy skin and jet black hair, pomaded and brushed back. His father George was a bricklayer, a gypsy, a nomad type, and I believe came from the Basque region in Southern France. Peerless is a rather unusual name and is probably derived from a French name. Mum’s name was Palmer, a good solid English (British) name. (Her father John had died before Alice’s marriage and her mother Minnie married Mr Breen.) He was a very distinguished looking gentleman, with a well- trimmed white mustache and beard. I remember Mr. Breen very well because he always wore black and had a silver headed walking stick, very popular in those days. And when he picked me up to kiss me, his whiskers tickled my face. Funny how one remembers some things so well, isn’t it.

My dad was not an educated man but was very wise in worldly things, and would tell wonderful stories of his travels at family gatherings, birthdays, and Christmas Eve, etc. Dad, I recall, worked at many menial jobs, painting houses, delivery man in a grocer’s shop and the like. He eventually became the Verger of All Saints Church (Church of England) headed by The Vicar E.G. Semple, and a blind curate, John Lewis. Dad was responsible for directing all church functions, weddings, funerals, etc., and leasing the church hall for dances, whist drives, etc. It was a good steady job for Dad, long hours, poor pay, but at least he was not doing manual labour as he had done for many years. Mum was not idle by any means. As well as raising twin boys, she had several jobs she did weekly. The custom in those days was to whiten the doorsteps of the rich people’s houses. This was done washing the steps (outside in the street, could be 1 or 2 or 6 or), then rubbing the steps with a block of whitening stone, that would dry a bright white. Average job would take about an hour. (Remember she carried a metal bucket & brush, etc. from our house to the job across the neighbourhood several times a day). For this she would be paid whatever the lady of the house felt like paying. She also black leaded stoves and fireplaces. Most cooking and heating stoves were made of cast iron and the custom then was to apply Black-lead (a mixture of carbon black & powdered lead) and when dry buff to a shine. Very dangerous material, but not known as such in those days. Again the pay was piddling and paltry, but enough to help them buy food for two boys, her and dad and pay the rent. But as you can see, life was not easy by any means, and the working class people (as we were called) really had a hard time existing at all. We all wore hand me down clothes we were given by the church, and I can remember stuffing cardboard in my shoes to cover the holes in the soles.

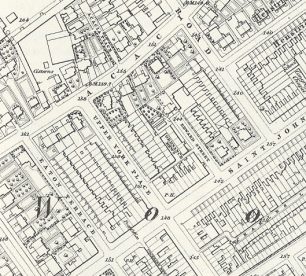

Our house in Aquila Street

When we were quite young the family moved to 2 Aquila Street, a four room London County Council house located at the end of a cul-de-sac off of St Johns Wood Terrace and one street off Ordnance Hill. There was an Off License on one corner of Aquila Street and a house on the other corner with a 6 feet high brick wall with broken glass bottles cemented along the top, I expect to keep kids or prowlers out. Our house was located way back in the left hand corner of the cul-de-sac, through a little wooden gate, up a path about 25 feet long. Turn left and there was the house, an oblong house, brick, with tile roof (slate) and two chimneys, one each end of the house. See sketch.

No heat except for a coal burning fireplace in each room, and coal being so costly, not too many rooms had had a fire lit at the same time. We basically lived in the kitchen located on the ground floor to the right of the front door. In there was an old wooden table, 4 chairs, a wireless battery (wet cell hydrometer), very dangerous if the acid contacted skin which it did quite often when revving up the set, a wooden shelf thing Dad made on one wall to hold food etc., and a cast iron stove that had a boiler and oven built in. The boiler supplied enough water to wash dishes, faces and hands, etc. The oven was large enough for the occasional chicken or rabbit pie. The fire in this unit was kept going day & night, winter & summer. Extra water was heated in kettles (cast iron) that were always sizzling on top of the stove, ready for the ever present “cup of tea.” The fuel, of course, was coal, which sat by the stove in an iron coal shuttle, with a small iron shovel in it, to add coal to the fire as needed. The coal pile itself was outside the house in the coal shed, a dark smelly, dank brick shed attached to the side of the outhouse. It also served as a storage shed & Dad’s workshop where he fixed things, and built wooden toys for us kids.

The kitchen

The kitchen was the main room of the house. The entire family revolved around the kitchen. It most certainly was the cosiest room there and in the winter definitely the warmest. Winter and summer it always had the most wonderful smells, cooking, bread baking, cake making, and at Christmas , mince pies. Those smells seemed to be locked into the very walls of that cosy little room. I can recall Mum cooking rutabagas, (swedes) my dad’s favourite vegetable. He would cook them over the stove & when cooked she would mash them with lard and pepper and put them on our plates steaming hot, and wow were they good. Same way with beets, except she didn’t mash them, just lard & pepper on whole steaming hot home grown beets, fantastic!!!! One thing, we ate well, not always the healthiest food, – lard, organ meats, brains, hearts, etc. Bread covered with drippings from cooked meat was our breakfast, lunch, and tea most days of the week. It was not known then of the devastating effect of the heavy fat diet would have later in life. Assuming that Mum & Dad did know (which of course, they didn’t), they could not have afforded any other kind of diet for us. Of course, certain times of the year we ate fruit from our garden, (Mum’s pet project) gooseberries, blackberries, black & red currants. The oranges we had were of course purchased from at the corner green grocer. Apples and pears were brought home by me or Dave after a “Scrumping” expedition! This consisted of “bunking” (climbing over a wall topped with glass of some wealthy person) and stealing fruit from their apple & pear trees. It was a risky business. Most yards with fruit trees had huge vicious dogs that only saw kids when they invaded their territory. But we would entice the dog off to one corner, feed it scrag meat, stolen from the butcher’s (Mountjoy’s) sawdust floor while one kid climbed the tree and picked off the fruit.

Washday

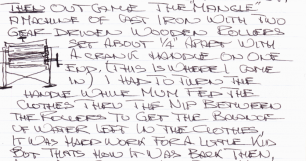

The little add-on section next to the house was a scullery. This had a “copper” which was a brick square, with a hole in the top in which sat an iron bowl about 36” in diameter and 24” deep. A fire was lit under the copper & water put in the copper. Soap was added and when the water became hot, dirty clothes were added and stirred around with a big stick to get the suds distributed throughout the clothing. Then Mum would take the clothes with real stubborn stains and rub them on the galvanized metal wash board. When the clothes were clean the copper was dipped empty with a bucket, and fresh water added, the fire stoked up and clothes added for rinsing. When the water became hot enough, then the clothes were hand wrung to get some of the water out. Then out came the “mangle” a machine of cast iron with 2 wooden rollers set about ¼” apart, with a crank handle on one end. (This is where I came in). I had to turn the handle while Mum fed the clothes through the nip between the rollers to get the balance of water left in the clothes. It was hard work for a little guy. But that’s how it was back then. After the clothes had been mangled (and I mean really mangled), they were carried in baskets to the rope wash lines in the yard where they were hung out to dry. When dry, the clothes were folded, put back in baskets and taken back into the scullery to await ironing. Everything one wore had to be ironed. No permanent press, etc. , and dependent on the weather, the ironing was done either in the scullery or the kitchen. But in either case, cast iron hand irons, two of them, had to be heated on the stove top. (Remember we had no electricity, only gas lights). In each room, a piece of pipe came through the wall. One tied a mantle to it (similar to a Coleman camping lite), then lit it with a match and tried to read or whatever with that meagre light. Mum and Dad preferred candles or oil lamps for everyday use, made it cosy, but not conducive for good vision.

After the hand irons were hot enough, the ironing began in earnest. Starch water was thrown or sprinkled on Dad’s & Mum’s shirts or blouses prior to ironing, then ironed to make everything smooth and stiff. What a gigantic job it was to do the washing then, compared to now. The weather in winter would be freezing. But clothes had to be hung out to dry. Sure they froze, but eventually they would dry, took several days, but they were left there until ready for ironing. I can remember seeing my dad’s long johns and my mum’s “bloomers” hanging on the line stiff as a board, blowing in the wind like a distress signal at sea!!!! One pair of bloomers would probably make 25 pairs of panties today!! They were huge. . . . . Anyway, thank goodness only one day a week was given to washing. Monday, 52 weeks a year—meant a lot of hard work for everyone.

I forgot to mention that there was no cold or hot water in the house—only one water tap (with a lead pipe) in the scullery, or wash house. And the scullery had no heat except on wash days. The water would freeze in the line, which meant in the winter we would walk to the end of the street (about a block) where the L.C.C. would have put a communal water pipe from the mains under the pavement (sidewalk). This tap was used by the majority of the people in St Johns Wood on really cold days (December thru Jan & Feb).

Bathnight

Bath night was Saturday every week. The copper was filled by bucket either from the cold water tap in the scullery or in winter from the street tap. Then the fire was lit. The water was heated as hot as possible (about an hour). In the meantime, a galvanized bathtub about 5’ 0” long 18” deep and 24” wide (with metal patches where dad had fixed no less) was placed in the kitchen in front of the black iron stove . Then the water was carried in bucket by bucket from the copper in the scullery and dumped into the tin tub. Then cold water had to be poured in (from the scullery tap or the street tap) until the water was the right comfortable temp for bathing. Then, the order of bathing was us first (Dave and I). Then the water was emptied out buy bucket and refilled as before. The next person in order was of course, Mum, then Dad. Dad used the same water that Mum bathed in. The whole ritual was performed in the warm cosy kitchen, lit by the coals in the iron stove and candles or oil lamps. Sounds cool, Eh? It was, but the lighting and heat were real, not there for effect as we do now, (you know soft lights and sweet music, etc., etc.). It’s all a very vivid memory to me. Everything is so impersonal and cold today. The involvement we naturally had as a family, by necessity, has gone forever.

The W.C., Lav was between the coal shed and the scullery, and had a water cistern that worked only part time. The brick walls were cold and damp and there was no seat on the toilet. It didn’t smell too good and if it was dark inside I did not like to use it. I hated to go in there because of the spiders and crawly little bugs. It scared the ??? out of me as a little boy and I never really got used to it as I grew older. Believe it or not, we used newspapers torn into squares for our toilet paper. First we would read it, then use it. It is a wonder we didn’t get sick from lead poisoning!

St John’s Wood shops

St. John’s Wood is a little part of London that has a lot of history going back many hundreds of years. It is right by Regents Park where royalty lived years ago, and many well-known artists, poets, actors, singers, members of the House of Parliament have lived and still do live in “The Wood,” as it is still called.

In the days of my childhood, if you needed meat, one went to the butcher’s shop, for peas or carrots, one went to the green grocer’s. No supermarket of course, but each merchant specialized in a few items. There was a baker, butcher, tobacco and chemist, also an undertaker. Everything was quite close to where we lived, and so walking to get stuff was a small chore. Items were purchased daily as the need became apparent. We had no way of storing any kind of food unless of course it was dry. There was no icebox or refrigerator, so getting things daily was a necessity, as you can see. But to go into those stores was a lot of fun. Each store had its own particular smell. Even today 60 years later, odours bring back so many good warm memories. For instance, the butcher’s shop (Mountjoys) at the end of the lane that ran behind St Johns Wood Terrace had a smell of onion and sauerkraut! Sawdust was spread on the floor to soak up the blood from butchered animals, and to make it easy to clean it up. The combination gave it and odour all of its own, not objectionable at all, as one might think, but quite pleasant.

Then the green grocer’s, with fresh vegetables of every kind laying on tables in and outside of the store for all to see. There were a lot of different odours and lovely colours. The store was owned by Mr. and Mrs. Salamoni. They came to England from Italy, and had about 10 kids. Some of their names I can remember, Angelina, Marianna, Peter, and that’s about it except Tony, who was about my age and we went to school together. The whole Salamoni family lived in the back of the store and it seemed that whenever I went by to see Tony, all the kids were sitting around this huge table eating pasta of some kind. It smelled good, but I can’t remember eating any or being offered any. The Salamoni girls were beautiful as youngsters and grew up to their teens with black hair, olive skin and lovely brown eyes. But as they grew older they blossomed into clones of Mrs. Salamoni who was 325lbs. Italian women tend to allow this. I guess their men like them heavy. But they were lovely people, very hard- working, honest and trustworthy. Tony’s older brother was always in some kind of trouble with the police, but I remember he finally grew up to be very responsible.

The there was “Bents” the chemist shop, on the corner of St. Johns Wood High Street and St. Johns Wood Terrace. A big door on the corner was topped by a huge gilded eagle with spread wings. The windows had huge strange shaped apothecary bottles filled with coloured water. I use to wonder why then, and still wonder why even today. The shop smelled of soaps, and was always rather frightening to a small child. It had high marble counters full of packages and bottles. There were huge glass cases with soaps, oils, lotions, potions and what have you. It was a whole potpouri of wonderful odours. I can’t remember the name of the chemist himself, but he was a huge tall man when he was behind those marble counters but, out in front, just a short, stout, man with a huge moustache and pleasant voice. My dad would always stop and chat with him if he was in the doorway when we passed. He was highly regarded in the neighbourhood, almost like a doctor was in those days.

On to the bakers, what wonderful smells of fresh bread and baking there were (Every day!) It was a very sparsely furnished shop with a baker’s oven barely visible from the front of the shop. There were wooden shelves with a case box with scones on the top. There were shelves on the walls and in the windows with all kinds of breads, cakes, chocolate eclairs, cream hornets and puff pastries. They had every imaginable fruit filling, such joy! We never got to eat such food unless other than Christmas (couldn’t afford to), but the visual treat, and wonderful smells were free. We savoured them every day on school days and Sunday on the way to Church. The name of the baker escapes me, but I remember the very pretty young girl that worked there before she became pregnant and caused one of the biggest scandals in the “Wood.” (People were not quite as “free”, then as they are now, and the poor girls had to leave the “Wood” in disgrace. What a bunch of sanctimonious bastards they were in those days)

The tobacco shop was run by a little man by the name of Gould. I went to school with his son. Jars of every kind of tobacco filled the shelves around a small counter with handmade shelves. The counter was glass and had shelves with wood, clay, and meerschaum pipes. They were beautifully carved. My dad would send me there twice a week for 1/2oz of shag and cigarette papers. They cost very little, and I guess that was probably one of the very few pleasures the man had. Life was very hard for Mum and Dad.

Then there was the undertaker shop. “Hurry’s.” was the name of the shop. What strange name for an undertaker. Mr. Hurry looked the part of an undertaker; tall thin, drawn face. He wore a silk top hat always, and a long tailed coat. His black horse and carriage was usually in the High street in front of his shop (ready for action) or was kept in the alley behind his shop. The carriage was really sharp, jet black lacquer everywhere and lots and lots of polished brass. In fact, it was polished everyday by either Mr. Hurry or one of his assistants. The front of the shop was where he displayed his ”boxes.” They were rather impressive and were made in the back of the shop. We would stand in the doorway of the shop and holler, “DO YOU HAVE ANY EMPTY BOXES?” Mr. Hurry would, of course, get angry and chase us away. I think every kid in the “Wood” when growing up, pulled that nonsense on Mr. Hurry.

The barber’s shop is where Dad would get a real deal, two haircuts for the price of one (for us kids). It would cost 6 pence (a Tanner), about 5 cents back then. We both had to go at the same time and with a huge pair of clippers on a flexible shaft (like sheep shears), the job on me and Dave was completed in a few minutes. I would hate it because the hair would fall down my neck and back and itch all day. This was usually done on Saturday (bath day).

The end of the story

Comments about this page

He also helped rescue my mother’s family, the Vincents, on the same day ! My grandma and her children were buried alive when their house in Aquila St collapsed in the bomb blast.

This is such a wonderful piece of writing and not only that..there’s a chance my great grandparents were helped by him when their house was bombed on Aquila Street in the war. I believe they had those nice steps and were located in the right side of the street (?) My great grandfather was also in India with the Military! It sounds as if they must have known each other..how exciting!

Add a comment about this page