Zeppelins and the blitz on London 1914 - 18

with special reference to St John’s Wood

Zeppelins

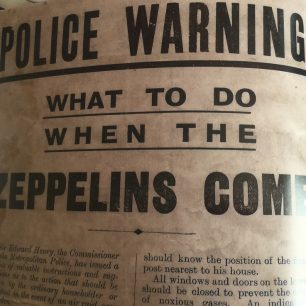

In 1900 the Germans began building Zeppelins – rigid steerable airships – and by 1914 had eleven of them, which they planned to use on bombing raids in the United Kingdom, to destroy morale as well as buildings. To begin with the Kaiser did not approve the bombing of London so it was not until 1915 that the capital was attacked, though even then historic buildings were supposed to be avoided. The arrival of zeppelins brought in the use of black out curtains and low street lighting as well as anti aircraft guns but these generally lacked the range and armament to hit airships which were extremely solid. This was helpful to the British in some ways, as rain added to the weight of the airship and made navigation difficult. On the 31st of May 1915 the first raid was carried out against London, mainly affecting Stoke Newington, killing seven and injuring thirty five.

Bombs on London

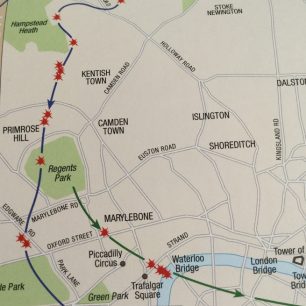

On September 3 1915 Zeppelin L19 reached London via Cambridge, passing over Golders Green, Finchley Rd and Primrose Hill and dropping a bomb in Woburn Square before going on to the City. 22 people were killed and the anti aircraft guns proved useless. On 8 September 1915 came the raid on central London by one Zeppelin, the L13, which not only caused more than half the material damage of all the raids in 1915, but was the most successful Zeppelin raid on London in the entire war, causing more than half a million pounds of damage.

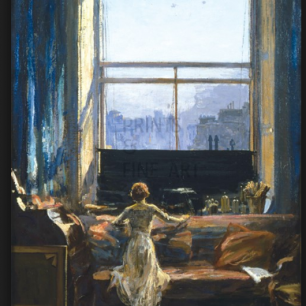

Two girls who were living in St Johns Wood Park during the First World War left a record of their experiences. Patricia Champness noted that the Observatory built by her great great grandfather John Edmund Gardner at No 28 meant that they could see Zeppelins as well as sunsets. During a raid Beatrice Curtis Brown’s family at No 4 went down to the kitchen which was almost below ground level. There were thuds from the bombs and a moaning scream and explosion from our own AA guns – there was one quite near in Finchley Road. The raids got less enjoyable as they went on. The cook used to sit and, with a kind of melancholy relish, tell us stories of disaster from the last raid. And after what seemed a very long time, the boy scout’s bugle would be heard signalling the all clear.

The British counter attack

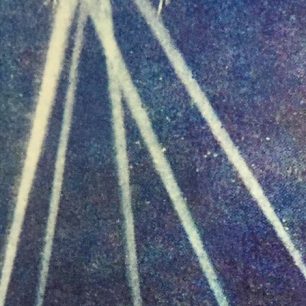

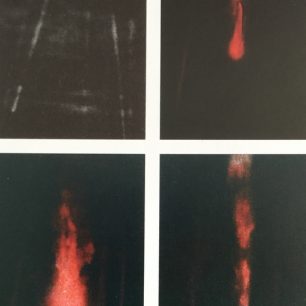

In 1916 there were now 2 gun rings round capital and 3 rings of searchlights beyond to greet the arrival of Super Zeppelins which were 650ft long. The zeppelin crews flew into battle with more than a million cubic ft of highly flammable hydrogen gas beneath them and the British developed machine guns with a deadly combination of explosive and incendiary bullets to which they added tracer bullets. Hydrogen is only flammable when mixed with oxygen and these bullets would blow a hole in the gas bags, allowing hydrogen to escape and mix with air, after which the incendiary bullet would ignite the mixture to deadly effect. The crew of a damaged zeppelin were face with the choice of burning to death or jumping to their death.

On 25 April LZ97 nearly reached London but was chased away by Capt A Harris (later “Bomber” Harris of the Second World War). On 24 August the Super Zeppelins reached London but not the heart of the City and on September 2/3 came the largest raid of war but it was disastrous for the Germans. SL 11 (an army Scutte Lanz airship rather than a zeppelin) was brought down by the new ammunition at Cuffley, Herts – the first crash on British soil that had no survivors. A vast crowd of Londoners watched from 30 miles away and Beatrice Curtis Brown heard a great roar which was the noise of Londoners cheering the first shooting down of a Zeppelin in flames. Bells rang, hooters hooted, trains whistled and army airships never came to England again. Some zeppelins did return but generally they had failed to deliver a killer blow. The network of searchlights and anti aircraft guns plus increased aircraft production had strengthened British defence but also made the British over confident that the worst was over.

Germany turned to aeroplanes for their attack

Few people realised that soon unopposed German bombers would be flying over the streets of London in broad daylight – hoping to attack morale, weaken industry and affect cross channel supplies. The first shock was the German aeroplane which dropped 6 bombs in Brompton Rd area on 28 November 1916, showing planes now had achieved the desired range to reach London.

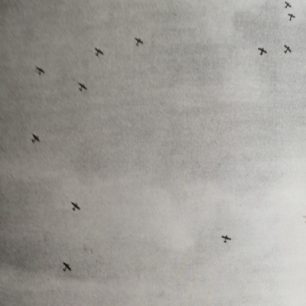

On 23 May 1917 came the first major aeroplane raid over London, when twenty-one twin engine Gotha bombers, armed with machine guns and carrying bombs up to 400 kg , were spotted but cloud and wind hampered them; then on 13 June 1917 came London’s first daylight raid when planes flew over Regents Park , then bombed the City killing 162 people and returned safely to the continent. On 7 July 21 planes reached London and 54 people were killed. Air Raid Warnings which had been banned in case they encouraged people to go into the streets to watch the aircraft were permitted at last.

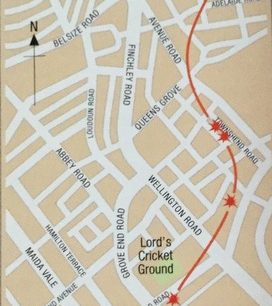

In September the Germans stopped daylight bombing and turned to night raids ; on 4 September seventeen bombs hit Primrose Hill and Regents Park. Barrow Hill School in St Johns Wood, which had been determined since war began that all scholars should “do their duty ” , reprimanded 30 girls at assembly the next day for arriving late. However parents did not all agree with this attitude and by October eighty girls were away from school, having been sent to safety in the country. Londoners began using Underground stations for shelter. On 19 October the last zeppelin to reach London flew down the Finchley Road dropping bombs in Hendon and Piccadilly.

7 March 1918 St John’s Wood hit again

In February 1918 the Germans produced a massive 1000 kg explosive bomb which was dropped on the Royal Hospital Chelsea and on 7 March 1918 bombs from giant four engined R.27 landed on Maida Vale and St John’s Wood. The Telephone Exchange in Townshend Road stands on the site of an earlier one which was demolished by a bomb from a Zeppelin. New Street (now Newcourt Street.) was hit by a bomb which demolished two houses, killing two families. Another bomb exploded outside Lord’s cricket ground, killing a soldier of the Royal Horse Artillery and a Lt Colonel on leave from Palestine. But far more devastating was the 1000 kg bomb carried by R39 and dropped in Warrington Crescent near Maida Vale. Rev William Kilshaw, living half a mile away and sheltering in his basement, wrote ” a terrific roar caused the whole house to tremble. Our top window panes fell to the ground with a shattering noise—we cautiously went to the window to behold a scene reminiscent of what one reads of the Great Fire of London. The sky to the east was lurid with flames in which dense smoke poured; the smitten district was afire.” The bomb went through the roof and dividing wall between No 63 and No 65 and detonated inside. The houses “all solidly built, were utterly wrecked”, another 20 buildings were seriously damaged and 400 slightly. Twelve people were killed and 33 injured – one of the victims was Lena Ford who had written the lyrics of Keep the Home Fires Burning in 1914.

The British were developing new planes, not without cost. On 8 June 1918 at Handley Page aircraft factory in Cricklewood they were doing test flights on an experimental bomber, the V/1500. St Johns Wood resident James Windebank from Violet Hill, an engine mechanic at the factory, was asked by the Captain to get on board so that they could do a flight with the projected full number of crew on board. During that flight the engines failed, and the plane crashed in Garrick Avenue, Golders Green, killing 5 of the 6 people on board, including James.

(with thanks to The First Blitz by Ian Castle)

No Comments

Add a comment about this page