Slave plantation owners

memorials in St John's Church

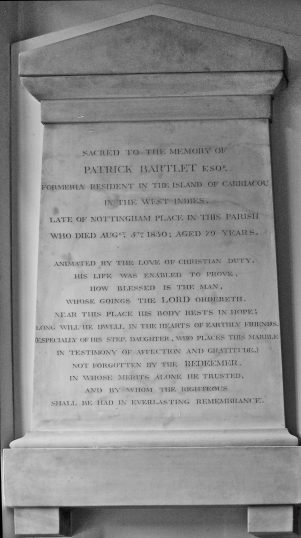

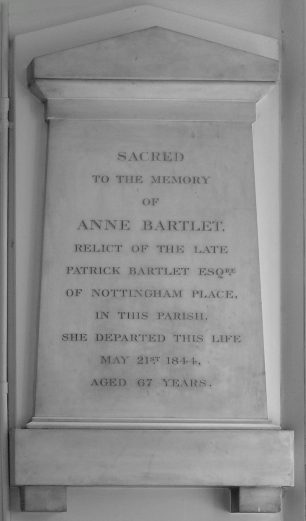

Four discreet memorial plaques in St John’s church give little idea of the intriguing histories commemorated there. One is to Mary and Richard James Lawrence of Crawford Street (died 1815, and 1830), one is to Jane Farquhar of Portland Place (died 1834). The others are to Patrick Bartlet of Nottingham Place (died 1830), and his second wife, Anne (died 1844). The clues come from the West Indian islands mentioned – Jamaica for the Lawrences, Antigua and Grenada for Mrs Farquhar, and Cariacou, near Grenada, for the Bartlets.

Marylebone and the plantation owners

On these islands were the slave plantations that provided the funds for a comfortable life in Marylebone, the newly developed area that attracted prosperous slave owners at the beginning of the nineteenth century. So much so that half the houses in the Harley street area were lived in by someone whose wealth came from slavery. In the 1770s a younger member of the family often managed the overseas property, while the head of the family remained in Britain. By 1775 30% of plantation owners were absentee landlords, and, by 1830, 80%.

Why Marylebone?

As their money came from commerce, these slave owners were not easily accepted in Mayfair. Slavery, itself, was not a bar to social acceptance since it had its basis in land, which, with its estate houses, attempted to recreate the life of the British landed classes. These estates were, frequently, heavily mortgaged, but there was often plenty of wealth to display. However, none of the islands were safe from the sudden descent of French attackers, until Napoleon was defeated, in 1815, so prosperity was not assured.

Why was slave labour needed?

Everyone in England wanted the benefits brought about by slave labour.

As Cowper wrote:

I own I am shock’d at the purchase of slaves,

And fear those who buy them and sell them are knaves;

What I hear of their hardships, their tortures, and groans;

Is almost enough to draw pity from stones.

I pity them greatly, but I must be mum,

For how could we do without sugar and rum?

Especially sugar, so needful we see?

What give up our desserts, our coffee, and tea!

Slave censuses were taken regularly by the owners noting names, ages, and distinguishing marks – presumably for identification if a slave tried to escape, – plus and annual return of decreases in numbers due to deaths, and increases due to births. [These can be found in the National Archives].

Life in Jamaica

English settlements overseas were usually financed and organised by private enterprise but Jamaica was different as it was seized by Cromwell’s army and captured from the Spaniards, in 1655. Spain, finally, relinquishing it in 1664

By 1700, Jamaica was awash with sugar plantations [70 in 1672, 680 in 1770], which were the only reason for Jamaica’s existence as a centre for human habitation.

At first, there were 7,000 English settlers to 40,000 slaves, then, by 1800, 21,000 English to 300,000 slaves. Each estate was its own small world with a labour force of field workers and skilled artisans, hospital, water, fuel, cattle, horses and mills, which were needed for crushing the cane. A typical estate of 900 acres would have a great house for the owner, and accommodation for domestic slaves; nearby were a bookkeeper, distiller, mason, carpenter, blacksmith, cooper and wheelwright. By mid 18 century, skilled black slaves had replaced white men in all these jobs apart from that of book keeper. Field slaves had living quarters ½ mile away, with vegetable gardens and space to keep poultry. Sugar [101,600 tonnes in 1805] and molasses rum were exported to England, and trinkets to Africa, from where the slaves were dispatched to the West Indies.

The Lawrences

John Lawrence, who had been a buccaneering commander under the privateer and, later, Governor General of Jamaica, Sir Henry Morgan, settled at Fairfield, dying in 1719 aged 46. He left Fairfield to his son, James Lawrence [d. 1756], who married Mary James, the daughter of the first baby who was born in Jamaica to English parents after it became a colony. James’ eldest son was Richard James Lawrence, who married Mary Hall, the daughter of Thomas Hall of Irwin, Jamaica, another plantation owner.

Richard died in London on 8 November 1830, aged 85, Mary having died in 1815. They had 5 sons, James (Sir James) who was a Knight of Malta, George, who made various trips to Jamaica to inspect the property there, Charles of Mossley Hall, Lancs, Henry, a barrister, and Frederick, a Captain and Gentleman of the Privy Chamber to Prince Regent. They used much of the compensation money to invest in new railways in England.

The Farquhars

Jane Farquhar was the wife of Robert Farquhar of Renfrew, who had inherited his Antiguan and Grenadian estates after the death of his half-brother, John Rae [afterwards Harvey), who had himself acquired them from John Harvey [1721 –79], after Harvey’s nephew, Charles, was drowned in Grenada. Harvey had made a handsome fortune in the West Indies, owning the plantations of Mornefendue, the Plain and Chambord in St Patrick’s parish at the north end of the island. The Farquhar’s daughter, Eliza, married Michael Shaw Stewart, 6th baronet.

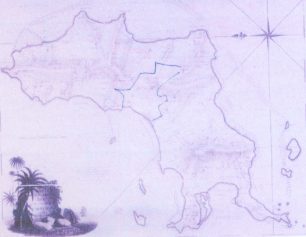

Carriacou

is an island 20 miles north east of Granada, measuring about 5 miles from north to south, and with a width varying between 2 and 5 miles, with an area of 13 square miles. It is hilly, rising to 954 feet in the south, and 955 feet at High North at the northern end of the island, and sugar was grown at lower levels. The only town in the eighteenth century was Hillsborough – otherwise the population was concentrated on the plantations.

Carriacou remained uncolonised by Europeans, until 1650, when a French company established a small settlement. The French had to cede it, with Grenada, to the British after the 7 Years War, in 1763, but recaptured it, in 1779, during the American War of Independence; there were only 90 British soldiers to guard it against 5,000 French invaders. However, it was returned to Britain after the Treaty of Paris, in 1783, and various gun batteries were built round the coast. French plantation owners, who had remained, were replaced by more English and Scottish settlers, and the larger estates expanded at the expense of smaller neighbours. By the 1790s, there were 46 estates ranging in size from 10 acres to 698 acres, but the important proprietors had interests in several plantations.

The Bartlets

Alexander Bartlet and George Campbell had formed a company that linked its offices in Grenada, Tobago and the Grenadines with London, and Alexander’s brother, James, was recruited to facilitate trade by persuading all the planters to consign their crops of cotton, cocoa, indigo and sugar to the company. Gradually, planters became indebted to Glasgow business houses, which led to foreclosures, and a general decline of planter aristocracy. Presumably, Patrick Bartlet [born 1730/31] was another brother, and must have lived on the island, probably, on the Beau Sejour plantation, which belonged to him, for, in 1792, he was recommended to fill a vacancy in the Council of Grenada, and was described as a principal inhabitant and proprietor.

Patrick Bartlet’s slaves in the various censuses were, also, on Belair and Belvedere. There was about 1 slave to every 2.35 acres, which gives a probable slave population of 3,153 and it is unlikely the white population exceeded 400. In the early 1790s, the Grenada Assembly passed an ordinance requiring there to be one white man to every 50 slaves.

Patrick’s first wife, Isabella, died, in 1821, and is also commemorated in St Johns Wood church. His second wife, Anne, (whom he married in 1824 at Warnford Surrey when she was about 47, and he was 74, or so), had long standing connections with the West Indies, as she was the daughter of Samuel Span of Bristol, Master of the Society of Merchant Adventurers, and a ship owner. Samuel, with his brother, had arrived on Union Isle, near St Vincent in the West Indies, in 1763, with 165 slaves and soon controlled the whole island, and, also, had property on Carriacou

Emancipation

The slave trade was outlawed in 1807, but slavery, as an institution, was not abolished until 1833. Compensation was then paid to owners, not to slaves, and under the Emancipation Act the slave compensation commission allocated 40,000 separate awards, costing £20 million – this was 40% of the total government’s annual expenditure. Only slaves under 6 years old were freed immediately, the rest were designated apprentices and finally released in 1840. After the emancipation of the slaves, prosperity on the islands declined as it was impossible with free labour to compete with sugar and cotton produced by slaves in Cuba and the Unites States, and then European sugar beet became a cheaper commodity. But Mrs Farquhar, the Lawrences and Patrick Bartlet did not live to see this outcome, and were buried in St John’s, [then] the chapel of ease for St Marylebone parish church, which had been positioned as the focal point at the top of a country lane running north from the New [Marylebone] Road.

Comments about this page

I have a question – do you have a record of a Mrs Mary Pearkes being buried in the chapel? She lived in Harley Street, her will proven 7 April 1822. She was born in Virginia and had slave connections.

An informative article, which I found while researching my family who are from Carriacou.

Add a comment about this page